Like many seismic events, you would be forgiven for not having noticed the gentle pre-rumblings about a change to the UK patent law which is due to come into effect in just a few weeks time. On July 28th the ‘Repeal of section 52 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988’ comes into force allowing industrial designers and their families the right to retain, reassert and legally protect the copyright of their designs for up to 70 years after the death of the creator. Previously limited to only 25 years after the design was released, the revision brings it into line with wider European law.

This repeal, which was lobbied by the powerful design community, is aimed at protecting industrial scale designs (where more than 50 copies of an object have been made) from open plagiarism within the retail market. It will perhaps correctly bring to an end the era of knock-off Corbusier, Eames and Egg chairs that currently flood the market place, yet by potentially reasserting protection on current and out of date designs (as well as having no exemptions for second hand goods), it could have important knock-on consequences for the secondary market. While the focus has been on furniture design because that is where most current patents seem to lie, the change is an umbrella one that could include anything from jewellery to home ware.

What will be affected?

The technical jargon from the Intellectual Property Office (IPO) is that the industrially produced design must be ‘a work of artistic craftsmanship’ to qualify meaning the form must clearly outweigh its function. The IPO acknowledges that their definition is open to interpretation which is worrying when you consider that every mass produced object of the last 100 years has been actively shaped by one designer or another. From cutlery to lamps, sideboards to bridges, we live in a world dominated by industrial design. Until now in the UK, our utopian principles have led to an accepted understanding that good design should remain available for the benefit of all and where plagiarism and subtle adaptations arose, these have always been a forgivable consequence of the industry. In 2011 it was estimated that the replica furniture industry in the UK accounted for only 7% of total UK furniture sales. Yet as European courts tightened their own legislation a few years back, the emerging internet allowed the UK to become a supposed hub for replica goods and push the onus back on the UK to tighten up as well.

How the Antiques field may be impacted

There are several ways that the antiques industry may be affected by the repeal and these changes have come about at a time when the interest in mid-century design is at its peak. Under the new rules any credible design produced since 1946 ( as well as some older ones still under contract) could potentially be covered by copyright. Although there will be a 6 month grace period until January 2017 to allow people to clear their stock or make necessary changes, the new law makes the sale of unendorsed design classics in the UK illegal. This change may bolster consumer faith and spending back onto the original vintage or endorsed items, yet will also surely see prices rise as well as the market thins out. It will mean that even as a private individual you won’t technically be allowed to sell your fake Corbusier armchair anymore even if you’ve had it since new from the 1970s. You will still be allowed to own it, but only officially produced versions by Cassina will be permitted for resale.

A second area that will affect the education, heritage and publishing industry the most is that the law will also apply to copyright protection on 2D photographic representations of such objects as well. Potentially hundreds of art, antique and reference publications may have to be modified and republished (at a cost to the publisher) to ensure there are no infringements made.

The Future

While the IPO feel the ‘artistic’ requirement of industrial design makes qualification for such copyright potentially hard to obtain, there is also no question that it will have long term impacts for many people. Already many interior designers are saying the change will push their costs sky high and magazines will have to be very careful when they are photographing on location. Publishers are facing massive short-term financial loss, and for their part auctioneers and dealers will have to be constantly vigilant for unofficial examples. It is the open-endedness that is troubling. The IPO say a design is protected due to its form and not its attribution. Therefore just because you do not know its makers name does not preclude it from protection. One wonders if all this uncertainty may actually push interest back onto genuine antiques which are free from such complications?

Last word

Unlike art, genuine uniqueness in the design world is actually a rare thing. Constrained by form and function, its a world instead of inspirations and subtle modifications towards the more perfectly balanced form. If the changes to the law mean the best of design becomes the preserve of the rich, then that sadly goes against the principles why many took to the drawing board in the first place.

For more information, relevant guidance is available via the www.gov.uk website or email section52CDPA@ipo.gov.uk

Chairs image attribution: by Boa-Franc

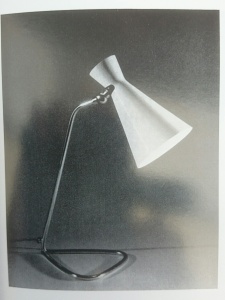

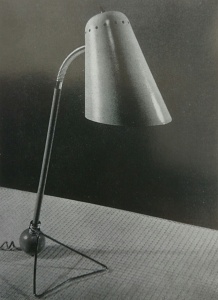

some time back said to be the best at anything, you just need to do the same as everyone else but 5% better. I would argue that in all but a few cases, top industrial designers are no different. Thumbing through a book I picked up recently confirmed this 5% rule to me. Though reprinted in 2012, the book was originally published in Germany in 1953. Entitled ‘Modern Lighting of the 50s’ the book showcases a wide range of lamps from the years just before 1953 from major designers and companies across Europe and America.

some time back said to be the best at anything, you just need to do the same as everyone else but 5% better. I would argue that in all but a few cases, top industrial designers are no different. Thumbing through a book I picked up recently confirmed this 5% rule to me. Though reprinted in 2012, the book was originally published in Germany in 1953. Entitled ‘Modern Lighting of the 50s’ the book showcases a wide range of lamps from the years just before 1953 from major designers and companies across Europe and America.